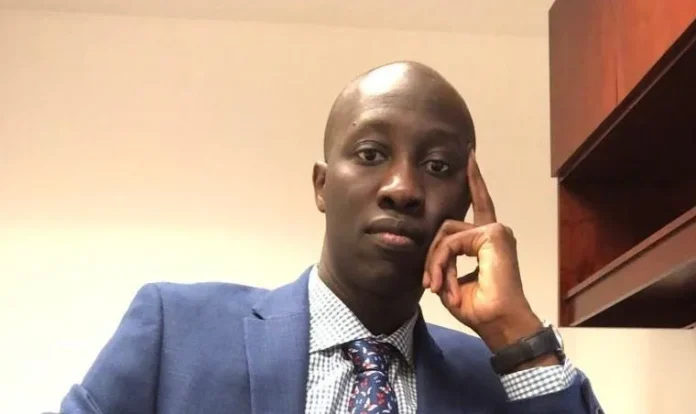

Sarjo Barrow Gambia Lawyer In The United States

By Sarjo Barrow, Esq.

The most important institution that should nurture and protect our nascent democracy is National Assembly (“NA”). Yet, the institution failed to attract talent or is considered irrelevant. But suppose the country is to learn anything during the past six years. In that case, NA can set the country’s trajectory, ensure efficient oversight, and require excellent service delivery because they control the country’s purse.

As NA deliberates and considers the Anti-Corruption Bill for enactment, citizens exert pressure on their NAMs to pass the legislation, and watching the debate on the Assembly floor was no fun. You can observe lawmakers visibly frustrated as they go back and forth with the sections and clauses. Frankly speaking, they find it hard to comprehend the bill or what it intends to proscribe. And considering most of the lawmakers do not have a legal background or adequate experience in legislation, arguably,the bill was over their heads. Notable among their fear or frustration is that the legislation may significantly legislate against the genuine Gambian culture of giving, supporting, and tradition. Rather than criticizing the shortcomings of the NAMs, it is imperative that we also offer natural and humble solutions or recommendations that the NA can consider during their sitting—the reason for this piece.

Some of the questions raised during the debate with the Attorney General (“AG”) are:

• Whether the phrase “any other person,” in section 19(1)(a),refers to an act between private citizens or to conduct such as giving to griots or hardworking traffic officers.

• Limiting the maximum fine to a million could cause loss to the state if the corruption involved is threefold the maximum.

• Should NA set a minimum fine when acts of corruption come in varying degrees?

And if it would be prudent to leave punishment open and trust the judiciary to do the right thing.

Instead of getting into the interpretation of 19(1)(a), I think the problem with the phrase is the result of the “copy and paste” syndrome. As such, I strongly caution NA not to remove the word but fix it. As written, the section states:

(1) A person who-

(a) asks for, receives, or obtains any property or benefit of any kind, directly or indirectly, for himself or herself or [for] any other person;

Inserting the word “for,” as done under paragraph (b) of the same section, would resolve the issue. As the heading suggests, the section punishes illegal official gratuities. Period. Adding the word “for” would mean that a would-be Defendant can still be prosecuted for receiving benefits on behalf of a third person.

Suggestions and Recommendations.

First, lawmakers should be trained in or familiarized with the country’s jurisprudence. This foundation would help them in drafting laws. For instance, if lawmakers know about the four rules of statutory interpretation, they will endeavor to ensure that legislative intent is clear even under the literal rule.

Second, although the bill addresses bribery in the private sector, the goal here should focus on public corruption. I think NA should revisit sections 19 and 20 before passing. The sections should address bribery of public officials and witnesses. For example, NA should divide section 19 into two subparts. Subpart 1 should address the giving and receiving bribes, while the other addresses illegal official “gratuity.”

As to the first part—giving or receiving bribes—the law should proscribe the conduct of the giver and receiver. For the giver, NA should require the AG to show that something of value was corruptly given, offered, or promised, directly or indirectly, to a public official. And for the recipient, NA should require the AGto show that something of value was corruptly demanded, sought, received, accepted, or agreed to be received or accepted by a public official. While NAMs raised legitimate concerns regarding the unintentional legislation of the Gambian culture, the intent required for the giver should be the intent “to influence any official act.” In contrast, the intent that should be necessary for the recipient is the intent to be “influenced in the performance of any official act.”

For the second part—illegal gifts to public officials—again, the conduct of the giver and recipient is being regulated. For the Giver, NA should require the AG to show that something of value was given, offered, or promised to a public official. As to the recipient, it requires a showing that something of value was demanded, sought, received, accepted, or agreed to be received or accepted by a public official. Here, the law should not require a specific intent to alleviate the lawmakers’ fear concerning culture. Instead, the unlawful gratuity must be “for or because of any official act performed or to be performed by such public official.”

Third, adopting this recommendation, as standard in contemporary jurisprudence, would distinguish conduct such as giving an “attaya” to a hardworking public servant from corrupting a public official with an “attaya.” How? The criticaldistinction between the bribery (receiving & giving) and illegal gratuity sections is that bribery would require a specific intent “to influence” a particular official act (in the case of the giver) or “being influenced” in an official act (in the case of the recipient); however, an illegal gratuity would only require that the unlawful gift be given or received “for or because of” any official act. Moreover, unlike illegal compensation, which can be forward- or backward-looking at a past or future official action, bribery would require a specific intent to give or receive something of value in exchange for a future official act—in other words, an explicit quid pro quo or direct nexus between the value given and a particular future action.

Moreover, as the current bill addresses it under section 19, the bill should clarify that the bribery and illegal gratuity offenses would not require an unlawful gift to be paid or even that the object of the illicit gift is attainable. The section should prohibitconduct as soon as an offer (in the case of the giver) or an acceptance (in the case of the recipient) has occurred.

Furthermore, I have a different view regarding punishment. Although the penalty for bribery should be more severe than an unlawful gift to a public official, to reconcile the fear of lawmakers that do not want corporations or individuals that commit serious financial loss/gain to the state to have a fine capped at a million, I think the approach below would strike a good balance. Since we can all agree that corruption is cancer killing our development and progress as a nation, the punishment must fit the crime. To this effect, the bill should put a minimum statutory fine of D50,000 for individuals and D250,000 for corporate bodies for bribery. For unlawful gratuity to a public official, a minimum statutory penalty of D10,000 for individuals and D50,00 for the corporation. The law should require up to 15 years for a prison sentence for bribery and up to 2 years for illegal gratuity to a public official.

Finally, the law would require that upon conviction, the person should be fined under this Act [the minimum] or not more than three times the monetary equivalent of the thing of value, whichever is greater, or imprisoned for not more than fifteen years, or both, and gives the judges the discretion to disqualify the individual from holding any office of honor, trust, or profit under the Gambia. See Election Act for similar sections. Indeed, I am open to helping NAMs draft specific areas regarding the Anti-Corruption Bill.

NOTE ABOUT THE AUTHOR: The Author’s practice focuses on constitutional law, national security law, and human and civil rights litigation.