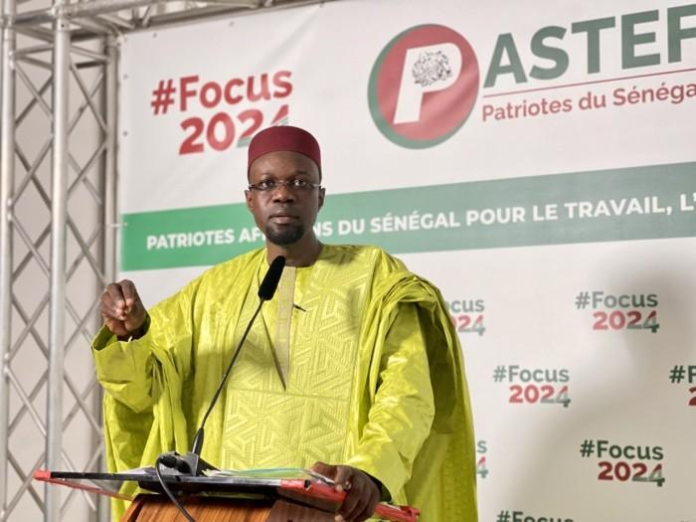

In the grandiose theatre of Senegalese politicking, where the archetypal David and Goliath reenact their eternal power struggle, a prodigiously inventive plot deviation has surfaced, echoing the audacity of Shakespearean drama and Machiavellian subterfuge. The governing authority, under the vigilant gaze of President Macky Sall, the Goliath of this enthralling saga, unfurled an audacious stratagem, teetering on the precipice of credulity: the dissolution of the opposition, captained by Ousmane Sonko, our political David. Comparable to a magician’s act of obliterating the troublesome rabbit from sight, they waved their political baton and, with a grand flourish, made PASTEF – Sonko’s party – evaporate into the ether. The scapegoat for this astounding act of political legerdemain? ‘Insurrectionary movements’ – a term brandished like a magical staff, held aloft in righteous indignation, its spectral apparition conveniently materializing each time the ruling power found itself cornered in the unrelenting spotlight of scrutiny.

This sleight of hand must have been conceived in clandestine meetings riddled with intrigue, whispered deliberations in the sanctified corridors of power culminating in this extraordinary decision. The eureka moment must have been akin to an epiphany: “A revelation, comrades! Why engage in intellectual duels with the opposition when we can make them simply… evaporate? Such brilliance in simplicity, one marvels at why this path remained uncharted until now!” With an orchestration rivaling a grand symphony, the government raised a righteous outcry of ‘insurrectionary movements’, casting Sonko and his PASTEF as the unruly protagonists. The term ‘opposition party’, it would appear, has become synonymous with an unwritten oath of subservience to every governmental caprice. Vigorous debate and accountability, the lifeblood of a robust democracy, are now portrayed as insidious harbingers of imminent anarchy, to be extinguished with an iron fist.

Frantz Fanon, the American bard and wordsmith, once articulated, “I feel in myself a soul as immense as the world, truly a soul as deep as the deepest of rivers.” Yet, it appears that the present government, usurping his wisdom, is meticulously laboring to drain these rivers should they dare flow against the currents of authority. Leopold Sedar Senghor, the venerated son of Senegal and a bard who envisioned democracy, must be tossing restlessly in his eternal slumber. His vision for Senegal, it appears, is being diluted by the current regime, which appears to be hell-bent on reducing the depth of these democratic rivers. Maya Angelou’s words resonate in these tumultuous times: “History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage, need not be lived again.” However, the government appears to have interpreted this wisdom to mean that history can indeed be circumvented, or even rewritten, if one possesses the guile to sculpt the narrative to fit the ruling party’s agenda.

Looming in the ominous shadows of grave allegations, Sonko stands resolute, unyielding in the face of adversity. His fate teeters on the precipice, with Lady Justice’s scales oscillating under the formidable weight of allegations as varied as they are severe. Yet hope persists, a glimmer in the apprehensive eyes of his steadfast supporters, buoyed by their faith in Sonko’s indomitable spirit.

The ruling camp, with eyes as keen as raptors’, scrutinizes these developments with a cocktail of anticipation, trepidation, and confidence. Sonko, in their narrative, is not the shepherd leading the youth to verdant pastures, but the pied piper enticing his followers down a treacherous path of instability. Amidst this tumult of political voices, Sall’sproclamation reverberates, a soothing melody promising a political metamorphosis that holds the potential to redefine the Senegalese narrative.

Accusations cascade upon Sonko like a relentless deluge upon an unsuspecting stone. Actions imperiling public security, seeds of profound political unrest sown, and a hinted predilection for illicit activities constitute a litany of accusations, culminating in the pièce de résistance: a whisper of unsavory affiliations with a covert terrorist entity. In this unfolding drama, the public prosecutor, Abdou Karim Diop, emerges with a startling revelation. Sonko’s portfolio of activities, tracing back to 2021, he posits, furnishes a damning collage of evidence against him.

This audacious balancing act by the government has launched the Senegalese political narrative into uncharted waters. Vital characters, even entire political parties, have been eradicated from the script with a swift stroke of the quill, creating a suspense-riddled saga. Is this the grand finale for the opposition, or merely an interlude before a more spectacular resurgence? As the curtain falls on this dramatic day, one can imagine government officials, a self-congratulatory toast in hand, savoring a predicament swiftly dispatched, conveniently swept under the ornate tapestry of politics. Yet, Robert Frost’s cautionary words echo in the wings: “In three words I can sum up everything I’ve learned about life: it goes on.” Life will indeed press on, with or without PASTEF, with or without Sonko. And perhaps, just perhaps, it will take unexpected detours, tripping the puppeteers of power and allowing the Senegalese people, the real actors in this grand narrative, to pen a different denouement to this political melodrama. As they say in the theatre, ‘The show must go on!’ Only time, and the unyielding spirit of the Senegalese people, will tell. In the land of Teranga, the story of democracy, it seems, is still being written.

By Modou Modou, Washington DC, USA